Timesheets: nobody’s favourite weekly (or monthly) ritual. You postpone them, consciously or not. Then the end of the month arrives, and suddenly your inbox is filled with polite-but-not-really-polite reminders: missing hours here, wrong project there, “could you fix this before billing closes?” Meanwhile at Raccoons, where we juggle client work, internal experiments, innovation tracks, and everything in between, correctly logged hours aren’t just admin, they’re essential. So it was about time we tried to make this chore faster, easier, and a lot less annoying. No better place for experimenting than in the Generative AI Playground: welcome back!

At our most recent Raccoons Day, a fellow Raccooner built an MCP (Model Context Protocol) server that connects directly to the Harvest API. Harvest is the time-tracking and project management tool we use at Raccoons, designed to help us log how long we spend on tasks, manage our projects’ budgets, and convert those hours into invoices.

In one day, the whole “ugh I still need to fill in my timesheet” problem transformed into a simple chat: “Yesterday I worked eight hours on project X.” Suddenly, time logging felt… almost enjoyable.

Below is how that came together.

Before we dive deeper into MCP servers and the Raccoons Day project, let’s take a moment to refresh our memory on what function calling actually is. For that, we’re taking a little trip down memory lane. Loyal readers (and Playground superfans) will surely remember this passage from Part 2 - Function Calling Moviebot:

Function calling allows AI models to interact with external tools and APIs in a structured manner. It enables developers to describe functions to GPT, which can intelligently output a JSON object containing arguments to call those specific functions. This process is dynamic and adaptive; the language model intelligently selects which function to execute and with what parameters at the appropriate times. The result of this function is then sent back to the language model, which can decide to invoke a new function with the results using new parameters and so on. This iterative process continues until enough information has been gathered through various function calls to generate an answer to the user's complex question.

So, simply said, we can get the model to generate text and execute specific tasks by calling predefined functions. For example, it can convert a user query like “What’s the weather like in Brussels?” into a function call that fetches real-time weather data, demonstrating the model's ability to intelligently navigate through a sequence of actions to provide informed responses.

The function calling workflow can be summarized in four basic steps:

The core idea is this: instead of letting a language model blindly guess how to interact with your systems, you explicitly describe what tools exist, what they expect, and how they behave. Why is that necessary? Because without schemas or definitions, a model really does have to guess. Yes, APIs follow conventions (like REST or GraphQL), but every system still uses its own endpoints, field names, request formats, naming quirks… and language models don’t inherently “know” any of that.

Even if they’ve seen a version of an API somewhere on the internet, that information can be outdated or incomplete. Ask a model to “create a time entry in Harvest,” and it has no reliable way of knowing whether the field is project_id, projectId, or id_project, or which fields are required, or how Harvest expects dates to be formatted. It’s like asking someone to submit a form they’ve never seen, in a language they don’t fully speak, and somehow hoping it magically works.

Moreover, even if the model did somehow guess the correct fields and formats, it still wouldn’t be able to execute the call on its own; it lacks the proper authentication and integration to actually connect to Harvest’s API. A random AI instance (say, ChatGPT on its own) cannot just invoke a protected company API without an authentication token and permission. In other words, beyond the guessing problem, there’s a barrier of security and access. The model needs a defined, authorized way to interface with the system. Function calling, combined with a proper integration layer, solves this by providing that structured, authenticated bridge between the AI and your real-world tools.

Function calling addresses these issues by letting you define a function with a name, description, input schema, and even an output schema. The model then uses that definition to construct the right API call. In other words, function calling acts as a translator between natural language and formal API logic: it turns a user’s request into a structured function invocation. Each function call is effectively stateless and one-off: the model decides at that moment which function to use and supplies the needed parameters, then moves on. This mechanism works great for simple tasks or quick integrations where you know ahead of time what functions the model might need to call.

And that brings us neatly to MCP. The Model Context Protocol is, in many ways, the grown-up, more ambitious sibling of ‘plain’ function calling. Traditional function calling is usually tied to a single assistant or environment: you define specific functions for a specific model or app, and the model can only use those hardcoded tools. MCP extends the concept into an open standard.

How does it work? Instead of defining functions for one model, you define tools with a standard schema and behavior, and any MCP-capable assistant (such as ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, Claude, Perplexity, or others) instantly knows how to work with them. Essentially, MCP becomes a shared language between LLMs and your internal systems, whether that system is an API like Harvest, a database, a ticketing tool, or any custom backend living somewhere behind your firewall.

In practice, an MCP tool is simply a well-described capability: “here’s what this tool does, here’s the shape of the input, here’s what the output looks like.” The model reads those definitions and knows exactly how to fill in the blanks. No ambiguity, no guessing, no trial-and-error. If the model needs to perform a sequence of actions, it can even chain these tools together (for example: first call a project-listing tool to find the project ID, then call a time-entry tool using that ID). We’ll illustrate this later with a clear example.

In essence, function calling and MCP work together. Function calling is how the AI decides what action to take, and formulates that action as a function call. MCP, on the other hand, is how that action actually gets executed in a reliable, standardized way.

It’s also worth emphasizing one of MCP’s biggest strengths: interoperability across platforms. Because MCP tools are exposed via a standard protocol, anyone on our team can interact with Harvest (or any system) through their preferred AI assistant or platform, all using the same MCP server. For instance, one of our developers might use an AI coding assistant integrated in VS Code (which supports MCP) to log hours without ever leaving the IDE. Meanwhile, a project manager could talk to ChatGPT or Google Gemini and achieve the exact same result through a conversational prompt. Both are leveraging the same underlying Harvest tools on our MCP server, with no extra integration work or custom coding needed for each platform. This “build once, use anywhere” approach is where MCP truly shines: it doesn’t matter if you prefer a chat interface, an IDE plugin, or another AI agent. As long as it speaks MCP, it can tap into the exact same functionalities.

MCP is still young (it was first introduced by Anthropic in late 2024) and it’s still evolving, but its potential is huge. At Raccoons, it meant that we could turn the tedious ritual of filling out timesheets into something surprisingly elegant (a simple message) by exposing our Harvest API through MCP. With the theory out of the way, let’s zoom in on how our own Harvest MCP server actually works.

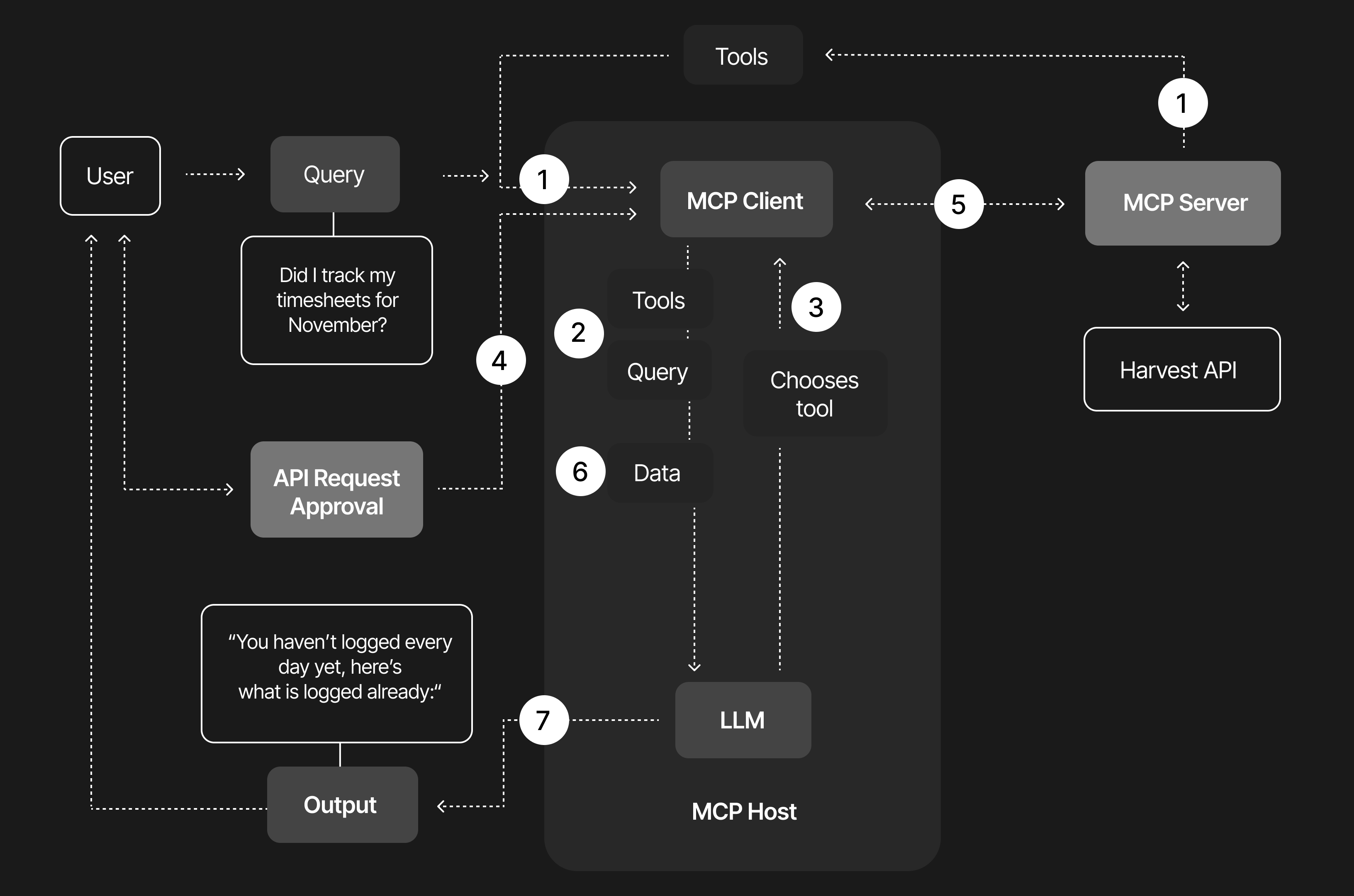

At its core, the MCP server sits between the LLM (our AI assistant) and Harvest. It translates the model’s requests into clean, predictable API calls and turns Harvest’s responses back into data structures the model understands. The magic lies in the strict input and output definitions. Instead of vaguely asking for “projects” or “hours” and hoping the model guesses the right API call, the model is given a tool description that explicitly states which fields exist, what is required, and how the response will look. The MCP-server becomes a polite interpreter that ensures the model never sends something Harvest cannot process.

In practice, when the model decides to use a tool (based on the function calling step we described earlier), it will produce a JSON request conforming to the MCP protocol. The MCP server then maps this to a real Harvest API request, executes it with proper authentication, and wraps the response back into the specified output schema before returning it to the AI. This way, the LLM doesn’t need to know anything about Harvest’s quirks or authentication details – it only needs to follow the schema and fill in the blanks. The server handles the rest behind the scenes, including using the correct endpoints and credentials.

To make this work, we defined all tools through Zod.dev, a TypeScript schema library that allowed us to describe every possible input and output with precision. By expressing each tool’s contract in Zod, we essentially taught the MCP server exactly what to expect and produce, and we provided the model a machine-readable spec of each capability. For example:

id and a name (and possibly nested tasks). The schema ensures those fields are present and of the correct type.By defining these through Zod, our MCP layer becomes self-documenting. The model can query the server for available tools, read the precise schema of each tool, and instantly understand which fields to provide and what output it will get.

We’ve already mentioned it: what makes this feel almost magical is how the model learns to chain tools together to accomplish a higher-level task, without the user ever needing to think about APIs or IDs. Imagine you’re interacting with the assistant in natural language while recording your screen. First, you simply ask it to log into Harvest. The assistant calls the authentication tool, receives a valid token, and proceeds. Then you ask, “Did I track my timesheets for November?” Behind the scenes, the model triggers the appropriate Harvest endpoints, aggregates all your entries for that month, and replies: “you haven’t logged every day yet, here’s what is logged already”, and then gently asks whether you’d like help filling in the missing entries.

You continue conversationally: “The 10th of November I had a day off, the 11th is a national holiday, and from the 12th to the 14th I worked for Zorg & Gezondheid on full-stack consultancy.” The assistant automatically resolves the correct project IDs, categorizes the time types, and calls the appropriate tool for each day. Harvest updates instantly, without you ever touching the interface. Then you remember: “Oh snap! Friday the 14th we had our monthly Raccoons Day!” The model recognizes the correction, locates the correct project for Raccoons Day, adjusts the already-created entry, and synchronizes everything with Harvest.

From the user’s perspective, all of this happens in an instant and invisibly. You just see a helpful confirmation. But under the hood, the assistant orchestrated multiple precise API calls on your behalf, thanks to the function calling and MCP framework.

At the moment, the MCP server still lives on a local laptop. It works beautifully in that environment, but it also reveals the next set of challenges we need to solve before making it widely available.

Harvest uses its own authentication model and MCP deliberately avoids prescribing a universal identity layer, so we need to design a clean approach for user-level access, secure token exchanges and safe scoping. We want a system where you can log your own time and only your own time, without giving assistants access to anything they should not see.

The power of MCP became crystal clear in just a single Raccoons Day: a future without those end-of-month “hey, don’t forget your timesheet” pings is finally within reach. That oh-so-monotonous task we all tend to put off might soon be as quick and effortless as sending a message. Once the technical foundation is fully in place, we can imagine every Raccoons colleague using their assistant of choice to handle timesheets without ever touching a UI again. No more clicking around or searching for the right project. You just say or type what you worked on, and your assistant takes care of the rest with polished precision.

With the Harvest MCP experience as a proof of concept, the horizon becomes wider. Any internal system with an API could, in theory, become MCP accessible. Time logging was only the first candidate because the pain point was obvious, but the pattern is general. Define the capabilities, describe the schemas and let the assistant do the orchestration. The Harvest server is only the beginning of what becomes possible when models and systems share a common language and a consistent way to interact.

If you want to know more about MCP, function calling, or this project: don’t hesitate to reach out. We’d love to chat.

Written by

Ward Poel